I read Frank Herbert’s Dune for the first time at the beginning of last year, and like many people I thoroughly enjoyed it. The world had a rich, handcrafted feeling to it, and the web of inter-faction intrigue was juicy and compelling. And with the new movie in the pop culture zeitgeist, I thought it’d be fun to revisit and old classic.

Dune the board game is a game of area control and political strategy for two-to-six players, although I think you’ll get the most out of the experience with four or five. In Dune, we command iconic factions in an attempt to control three of the five “strongholds” on the planet Arrakis by collecting spice, deploying soldiers, making deals, and sometimes even breaking a few. It’s a heavily strategic game where every move you make counts, where your success hinges on your ability to manipulate pieces on the board as well as your fellow players.

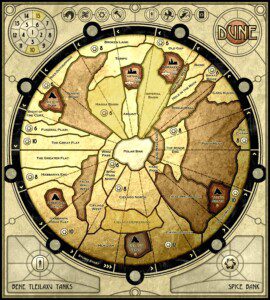

Mechanically, Dune has no large rules, just lots of interconnected little ones. The number of rules can make the first game or two a little daunting, but trust me, they can be boiled down to a pretty simple gameplay loop: a) move the sandstorm around the planet, destroying everything in its path, b) flip cards to determine where spice (the in-game currency) appears, c) give a little spice to the broke players, d) blindly bid on cards that give you special powers, e) spend money to resurrect fallen soldiers, f) deploy new soldiers or move current ones, g) FIGHT!, h) collect spice, and i) check to see if anyone has won the game.

It sounds like a lot, but the meat of the game happens in steps d, f, and g. Everything else is essentially game admin, and can be done in about thirty seconds.

What I love about Dune is how the relationship between players and factions aren’t solely social. Each faction has their own rules for how they interact with the game. The Atreides get to look at the facedown cards we’re all bidding on, and can keep notes as to who is holding what. The Harkonnens can hold more cards than any other player! And whoever wins a card doesn’t pay their winning bid to a bank, no, their spice goes to The Emperor. Want to ship dudes down to the planet? You pay the Spacing Guild. Want to move your dudes from one patch of sand to the next? They’re going to have a rough time, unless you’re playing the Fremen, because of course  the natives of this planet know how to move around it! There’s even a faction of space witches, the Bene Gesserit, who, before a game starts, can write down a faction and a turn number on a piece of paper, and if that faction wins on that turn, the Bene Gesserit win instead! (This hasn’t happened in one of my games yet, but I eagerly await the day.)

the natives of this planet know how to move around it! There’s even a faction of space witches, the Bene Gesserit, who, before a game starts, can write down a faction and a turn number on a piece of paper, and if that faction wins on that turn, the Bene Gesserit win instead! (This hasn’t happened in one of my games yet, but I eagerly await the day.)

This system of paying other players to buy cards and deploy troops works for me. It creates this internal game economy that not only makes sense narratively, but requires a new dimension of risk assessment. Of course I want access to these resources, but the more I invest in them the more money I’m giving to other players, which gives them access to those resources too.

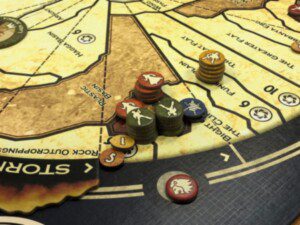

The combat is a nice departure from regular war games as well. In games such as Risk or Axis and Allies, engaged forces roll dice to determine success. Not in Dune. In Dune, we have these wheels in place of dice. In secret, we dial in a number (up to and not exceeding the number of soldiers we have in that fight), add a leader to boost that number, maybe add a power card or two if we’re feeling confident, and then reveal. First, we check to see the effects of our cards, then we determine who has the higher number, and that player wins the fight. But here’s the rub: the number you dial is how many soldiers you’re willing to lose. Everyone on the loser’s side dies, but if the winner has committed all of their soldiers to that fight, all of their soldiers die as well, and the desert goes back to controlling that territory.

Bloodshed can be avoided though. At the beginning of the game, each player is given one traitor card (The Harkonnens get four… play as The Harkonnens). If you’re in a fight, and your opponent commits the leader on your card to that fight, you can reveal that leader as a traitor and win automatically. Your soldiers survive and the enemy is pulverised, humiliated, and bitter. There is an almost sadistic joy you experience when revealing that an opponent’s leader is a traitor. In seconds you see the stages of grief flash through their eyes – denial, anger, depression – and with a frustrated sigh they resign themselves to their loss, while you sit there quietly pleased that this battle cost you nothing…

Dune, I think, is a game for people who enjoy strategy war games first and foremost, but it’s also for fans of the book, and there’s something nice about that. A strategy gamer might play it and then may be interested in reading the book in the same way a fan of the book may play it and be encouraged to play more strategy games. And if you’re both, you’re going to feel right at home. This game was literally made for you.

Dune is a slow-burn. It’s an event. When you play it, you don’t invite your friends over to “play some board games,” you invite them over to “play some Dune.” And frankly, it’s an enjoyable event. Bring snacks, have a meal with it, get into character if you want. Roleplay, be despicable, be heroic, be honest, be treacherous, feel elated when your risk goes your way, feel betrayed when one of your leaders turns on you. Plot, plan, conspire, have fun.

If you’ve played meaty games before, give Dune a hot crack. If you’re a fan of the world, this game is at least worth a look. I enjoy it, and you might too.