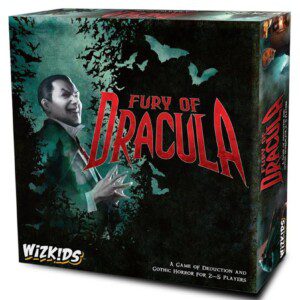

Have you ever wanted to traipse around 19th-century Europe with a group of friends, unearthing and foiling the malevolent machinations of your other, much older, more powerful friend? Yes? Well, that’s an oddly specific dream you have, but thankfully Fury of Dracula has you covered. And, from me, it’s a game that comes recommended highly.

Fury of Dracula is a game of cat-and-mouse for 2-5 players (although for the best experience, I recommend playing with at least four). Set within the throes of an ever-darkening Europe, one player takes on the role of Dracula, while everyone else takes on the role of a vampire hunter. Dracula wants to survive long enough to score thirteen influence – which he does by creating new vampires and advancing other schemes – and the hunters want to, ideally, find and kill him before that happens.

The main gamepiece is an old-timey map of Europe, dotted with locations that are connected by road and rail. Dracula has a deck of cards each marked with one of these locations, and it is from this deck that he will choose his starting location, and so create the trail. With that first piece in play, the hunters are ready to begin their hunt.

Fury of Dracula is played in phases – day and night – with hunters acting during both and Dracula only acting during the night. During their turn, a hunter gets to do something from a list of actions that include getting gear, resting, searching cities, and preparing for future turns. A hunter can move between cities during the day but not during the night, as this is when Dracula’s minions are abound, and it isn’t safe. Between them, hunters are trying to pick up on Dracula’s trail, and they are encouraged to communicate with each other and coordinate their actions to achieve this. However, unless two or more hunters occupy the same city, all planning must be done publicly. This means that Dracula is also privy to what the hunters have in mind.

On Dracula’s turn, he will select another location card from his deck and add it face-down to the trail. He will also enact a scheme at that location from a hand of encounter cards, which, if the hunters don’t discover and stop it in time, will mature and score him the influence he needs to win the game.

A game of Fury of Dracula starts rather slowly, as the hunters stumble blindly around the map and Dracula gets the wheels of his evil plans spinning. However, the more turns Dracula has, the larger the trail he leaves is, and the more likely the hunters are to pick it up. And picking up the trail is inevitable. When a hunter moves into a city where Dracula has been, Dracula must reveal that city’s card if it’s still on the trail. Whenever I’ve played this game as a hunter, there is a collective whoop! when this happens. Now we know where Dracula has been, we can deduce where he is. The hunt is officially on.

For the Dracula player, when your trail is discovered there is a twinge of fear. Suddenly all the power you’ve had is diminished, and you’ll find your mind whirring as you desperately try to shake the hunters off your scent. Thankfully you’ve been laying traps for the hunters, from saboteurs to new vampires, and if the hunters pick up your trail you can either ambush them with your traps as soon as they enter the city, or you can leave them to discover it themselves.

As a hunter, it’s a brain burn as all of you throw around possible routes Dracula has taken to his hypothesized current location, and why he would have taken that route. As Dracula, the puzzle becomes weaselling your way out of the hunter’s grasp. Oftentimes the hunters will drop in and out of following and then losing the trail, and it creates this tension where everyone knows just how close the enemy is, but not exactly where. It’s a tug-of-war, it’s a race against time, and I find it really compelling.

But all of that deduction is only half the battle. After all, once Dracula has been found he must then be killed for the hunters to win. And Dracula isn’t the only one the hunters will be fighting. If a hunter enters a city with another vampire, the gloves are off, and a fight will happen.

Combat in Fury of Dracula plays a little bit like rock-paper-scissors, and there’s an element of luck involved that some people might not like. To fight, the hunter and the vampire (i.e. Dracula) will each pick a card from their hand of combat cards and simultaneously reveal them. Each combat card has some icons and an effect. First, we check to see if the icons on the hunters combat card much that of the vampires. If they do, the vampires attack is cancelled, and the hunter resolves the effect of their card. If they don’t, the effects of both cards are resolved, with the vampire’s being resolved first. This combat system is undoubtedly tense, as both players are trying to anticipate what the other will do and hoping their gambles pay off, but ultimately that’s all they ever are – gambles. Personally, I’m not bothered by this luck aspect. I find there’s a level of social deduction in a combat encounter, and enough information is there to make an educated guess as to what card is the best to play. That said, some people mightn’t enjoy the lack of a definite, optimal action.

Combat in Fury of Dracula plays a little bit like rock-paper-scissors, and there’s an element of luck involved that some people might not like. To fight, the hunter and the vampire (i.e. Dracula) will each pick a card from their hand of combat cards and simultaneously reveal them. Each combat card has some icons and an effect. First, we check to see if the icons on the hunters combat card much that of the vampires. If they do, the vampires attack is cancelled, and the hunter resolves the effect of their card. If they don’t, the effects of both cards are resolved, with the vampire’s being resolved first. This combat system is undoubtedly tense, as both players are trying to anticipate what the other will do and hoping their gambles pay off, but ultimately that’s all they ever are – gambles. Personally, I’m not bothered by this luck aspect. I find there’s a level of social deduction in a combat encounter, and enough information is there to make an educated guess as to what card is the best to play. That said, some people mightn’t enjoy the lack of a definite, optimal action.

Who would I recommend Fury of Dracula to? It isn’t a casual game. There are quite a few rules, and the game can take anywhere from one to three hours to play. So it’s a commitment, and it isn’t light. But I do find it kind of charming. I love the theme and I’m compelled by the hunt. The social element of tabletop gaming lends itself to this game, and there’s a competitive experience around it that feels fair. Yes, luck is involved in some small way, but there’s no situation you can’t get out of if you’re clever enough. And I guess in that way, it’s a battle of wits.

If yours is a family or playgroup that are pretty well-versed with board games, this one is worth considering. If you enjoy social puzzles, cooperative games, chases, races, and pale boys with pointy teeth, I reckon this game would fit nicely on your shelf.